Maria Luiza Falcão Silva

Joaquim Pinto de Andrade

October 2021

According to the joint action plan of the strategic partnership between the governments of the Federative Republic of Brazil and the People’s Republic of China, for the period 2015-2021 (article 5, paragraph 5), it was established that the two sides would continue to work together to promote sustained growth in trade and in two-way investment, striving to increase and diversify bilateral investment flows and to improve and intensify trade and economic cooperation between the two countries. The two parties pledged to work for industrial cooperation in priority areas, such as aviation, auto parts, transport equipment, oil and gas, electricity, railway, highways, airports, ports, storage, transport, mining industry, agriculture and livestock, food processing and services (especially in the high-tech and high added value sectors).1

The question is: Besides the intent expressed in terms of the strategic partnership, does Brazil have any plan to receive Chinese investments for the benefit of the national economy, or are we simply following the strategies outlined by China?

Understanding the nature of Chinese investments in Brazil

Direct investments by Chinese companies in Brazil augmented substantially from the first decade of the 21st century and on when, some Chinese companies, in different sectors, after going through a period of technological learning at the internal level, became efficient, productive and ready to trans nationalize. The Chinese State provided the volume of capital necessary for these companies to become big enough to compete in the global economy, through the State controlled financial markets. Opening-up its capital market, in the last two decades, was inevitable for China following its entrance in the World Trade Organization (WTO) and struggle to be recognized as a market economy. But, given the strong presence of the State in all senses, China’s model cannot be compared with liberal or neoliberal models. After all, control belongs to the Chinese Communist Party and not to the “market forces”.

A survey prepared and released by the China-Brazil Business Council (CEBC) reports that total Chinese investments in Brazil reached US$ 66.1 billion in the last 14 years. Between 2007 and 2020, Chinese companies invested in 176 projects in Brazil and the country received 47% of China’s investment in South America.2

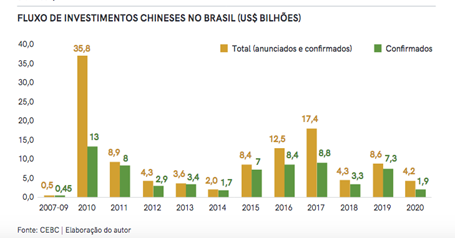

From Graph 1, it can be inferred that Chinese investments practically started in 2010, during Lula’s presidency, when US$ 35.8 billion in investments were announced and US$ 13 billion were confirmed. The historical series has its biggest reduction in 2020, due to the worldwide retraction in the flow of international investments, largely due to the sanitary crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, when the flow of Chinese investments to Brazil reached US$ 1.9 billion compared to US$7.3 billion in the previous year. The 2020 result occurred in a context of a general direct international investment retraction of 50,6% suffered by the Brazilian economy.

In 2019, the inflow of net direct investments into the Brazilian economy was on the order of US$69.17 billion, falling to US$34.17 billion in 2020. It was the smallest inflow of direct investments to Brazil in eleven years. In 2009, it achieved US$ 31.48 billion.

Graph 1: Flow of Chinese Investments to Brazil

Fonte: CEBC

The CEBC survey highlights that 70% of the value of Chinese investments confirmed, between 2007 and 2020, entered Brazil through mergers and acquisitions, reflecting the Chinese State’s strategies to expand its capital to the Rest of the World, according to its strategic objectives, including the relationship with private and state companies from other countries.

In 2010, Brazil was the destination of 25% of all Chinese acquisitions abroad, something around US$ 13 billion. The percentage dropped in the following years and gained momentum as of 2015, when the recession made Brazilian assets cheaper and the “lava jato operation”3 practically destroyed the main Brazilian civil construction companies, responsible for major infrastructure works in the country and many abroad.

The period portrayed is quite significant given that it covers four governments: Lula (2003-2010), Dilma (2011-2016), Temer (2016-2018) and Bolsonaro (from 2019). What attracts attention is that the behavior of investments is cyclical, with descending peaks, regardless of the alignment of the Brazilian State with the Chinese, in different periods.

The expansion of the world economy in the first decade of the 21st century and the Lula government’s position of international insertion of the Brazilian economy via South-South policies seems to have influenced the explosion of projects announced in 2010. The euphoria with the discovery of the pre-salt also influenced. The idea of a South-South relationship was that all parties would benefit (a win-win game). It was going to oppose a relationship along the imperialist lines of North-South relations. This narrative was easily absorbed by a large part of the left-wing point of view, especially during the Workers’ Party (PT) governments, which needed to give urgent answers, without breaking the prevailing system of power, to enable economic growth in a situation of strong concentration of income and wealth and of social exclusion. China, in turn, was undergoing profound changes in its economy in the second decade of the 21st century and was adapting to the capitalist world in crisis since 2008 and, in this sense, access to oil, guarantee of grains and animal proteins was vital for the “Chinese-style socialism construction”. The enthusiasm was so great that in 2014, Dilma signed agreements with China that involved US$ 53 billion in investments through 35 bilateral agreements in the areas of planning, infrastructure, trade, energy, mining and others, including those with Petrobras marketing and loans from 7 to 10 billion dollars. China also proposed to finance, through the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (IBCB), US$ 50 billion in infrastructure constructions such as ports, airports, railways, highways, housing and renewable energies. The coup d’état that removed President Dilma from the government stopped most of these initiatives.

With the impeachment of President Dilma in 2016, speculation emerged that there would be a setback in relations between Brazil and China, which had already become one of Brazil’s main partners, both in terms of trade relations and in terms of source of foreign investments for the country. The argument was that this proximity was based on a political and ideological alignment between the PT and the Chinese Communist Party (PCC). But that was not what happened, pragmatism prevailed. Neither the right-wing government of President Temer nor the Chinese created obstacles to the continuation of the partnership.

In 2017, under the presidency of Temer, China led the ranking of acquisitions in Brazil, reaching US$ 8.8 billion, declining to US$ 3.3 billion in 2018, and reaching US$ 7.3 billion in 2019. Under Bolsonaro, there was a substantial decline, but the reason does not seem to be the president’s numerous attacks on China, for the most foolish reasons that need not be pointed out.

Chinese investments in fact fell in 2020, under Bolsonaro’s government, reaching US$ 1.9 billion. It can be argued that after 2017, China’s investments have declined worldwide.

In recent years this trend was intensified by the pandemic, which has led China to focus on the domestic market. In 2017, the global total Chinese investments abroad exceeded US$ 255 billion but dropped to US$ 64.2 billion last year. In Brazil, the drop in Chinese investments was even greater proportionally, from US$ 8.4 billion in 2016, to just US$1.9 billion in 2020. Nevertheless, as pointed before, it does not seem to be due to Bolsonaro team’s hostility towards China because, along the same period, Sino-Brazilian trade flows have substantially increased, despite the pandemic, exceeding US$100 billion in 2020. The recent shrink of the flow of investments apparently has to do with a new reality of slower growth in China after decades of robust economic growth and recent policies aimed at the domestic market and welfare of its population, with a change of previous development strategy based on strong participation of investments abroad and export performance.

But back to Brazil, what can be argued is that all the governments examined so fare are, in reality, under the control of country less financial capital, represented in Brazil by the “Faria Lima”4 as the ruling elite is usually called. The main concern of this elite is to earn ever larger profits and not to fight ideologies. None of Brazil’s governments in the first two decades of the 21st century broke with the neoliberalism that has prevailed in the capitalist world since the 1990s. For some, as in PT governments, the State is more active, state-owned companies in the oil, gas and electricity sectors are seen as strategic (Petrobras , Eletrobras, etc) and the action of the State – as inductor of growth and agent of income redistribution – is recognized as fundamental. Public banks are considered as essential to leverage companies to become more competitive in the process of internationalization of the economy. Developmentalist models are implemented, as in the Lula administration and, to a lesser extent, in the Dilma administration, with larger concessions in the second term to the “Faria Lima” group, to avoid the coup d’état that culminated with the impeachment of President Dilma. The other governments of the period, under the presidencies of Temer and Bolsonaro, presented themselves as liberal and sought to reduce the role of the State, defending privatization and/or public-private partnerships under the aegis of financial capital.

The presence of China in Brazil, in our opinion, must be analyzed from the dynamics of China’s growth and its insertion in the international economy, and not from the perspective of development models being implemented in Brazil with the bless of the ruling elite, or from Brazilian foreign policy strategy.

Let’s see what we can infer from the sectors in which China has invested in Brazil.

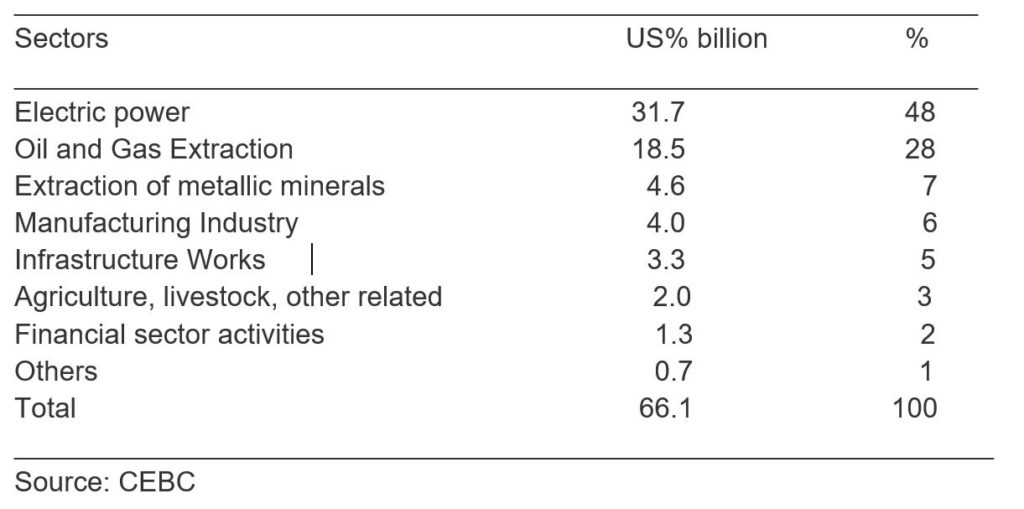

Table 1

Distribution of Chinese Investments by Sectors 2007-2020

According to Table 1, most of the US$ 66.1 billion invested in the last 14 years (2007-2020) by China in Brazil follow the pattern that has been recurrent in the rest of the world: i) access to natural resources, (ii) search for commodities to support China’s incredible growth rates. About 48% of the total invested were directed to the electric energy sector, in which there is a presence of large Chinese state companies such as State Grid and China Three Gorges. China General Nuclear Power Corporation (CGN), a large clean energy corporation under the supervision of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of the State Council of China, is another good example. Oil and gas extraction follows, representing 28% of the total invested. In this case, the presence of Chinese National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) stands out. Chinese National Petroleum Corporation, controller of PetroChina is partner of Petrobras in the pre-salt, thanks to the joint acquisition in the auction of the Libra field. Extraction of metallic minerals (7%), manufacturing industry (6%), infrastructure (5%), agriculture, livestock, and related services (3%) and financial services activities (2%) adds to 23% of the total Chinese investments in Brazil, in the period that extends between 2007 – 2020.

In 2017, China Merchants Group, a company also controlled by the Chinese State, acquired the container terminal at the Port of Paranaguá and, in the port area, this time in the north, in Maranhão, the state-owned China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) has invested in the construction of a port to transport agricultural exports.

Therefore, it can be concluded that Chinese investments in Brazil are mainly related to the natural resources sector (energy, mining, agriculture), with a smaller part directed to the infrastructure sectors, such as the energy distribution and transport, some to consumer and capital goods and into the financial area. For Brazil matters to investigate how this set of investments can be translated into more investment in infrastructure (roads, railways, ports, airports) for the flow of Brazilian production as a whole – within the country and in international markets, today practically restricted to the highway network of inadequate quality. A good infrastructure, logistic and transport base are factors that drive development in any country, and especially in countries with continental dimensions such as Brazil.

The logic that drives the expansion of China’s direct investment in Brazil is no surprise. It points to the search for profits from the internationalization of its monopolistic state-owned companies, ensuring markets for its industrialized products and guaranteeing the supply of raw materials, food, and energy sources to sustain its fast-growing projects that already place China as the second largest Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the World economy.

Investments linked to agriculture draw attention for their low value, 3% of the total, which contrasts with the great complementarity between the two countries in this area, which led to a large growth in foreign trade. In 2020, China became Brazil’s first trading partner with a flow of bilateral trade over US$100 billion. The trend of trade flows reenforces our argument.

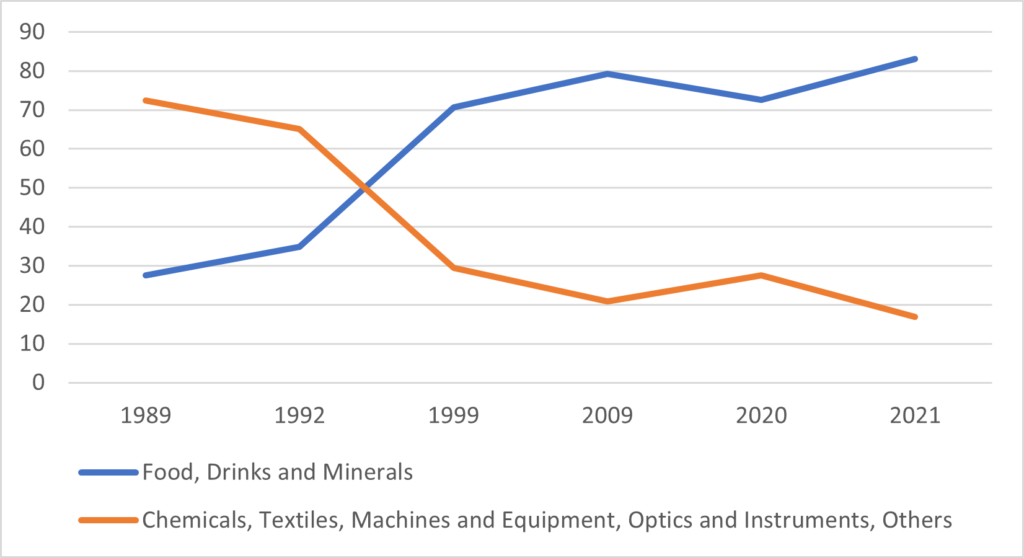

Graph 2, for instance, indicates that the share of primary goods, showed very high growth rates in the composition of Brazilian exports to China – increased from less than 30% in 1989 to more than 80% in 2021. Along the same period, the share of manufactured goods dropped from more than 70% in 1989 to less than 20% in 2021.

Graph 2

Composition of Brazilian Exports to China (%)

Source: Ministry of Economy/Comex Stat – Author’s elaboration.

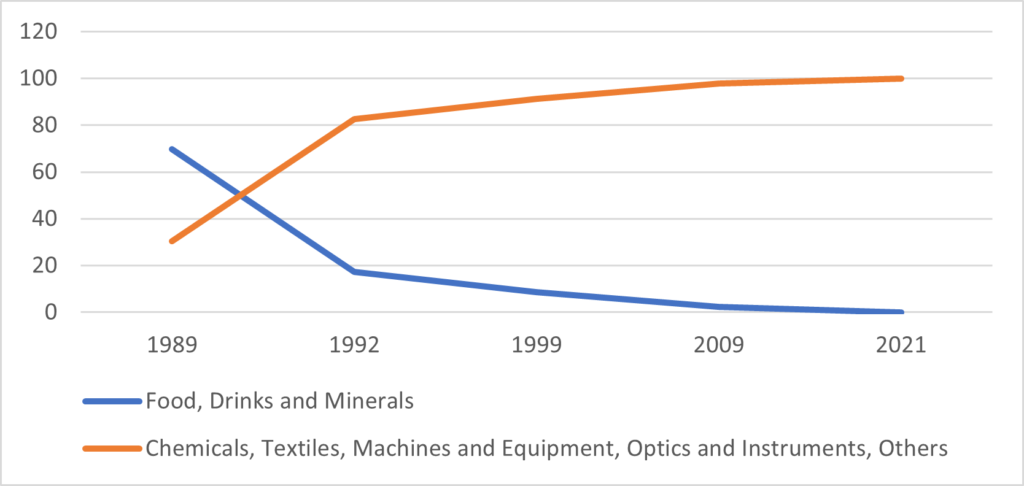

From Graph 3 can be depicted that Chinese exports to Brazil behaved in the opposite direction – exports of manufactured goods increased from around 30% in 1989 to 100% in 2021, and primary goods dropped from around 70 % in 1989 to almost disappearing in 2021.

Graph 3

Composition of Chinese Exports to Brazil (%)

Source: Ministry of Economy/Comex Stat – Author’s elaboration.

Trade flows and investments in Brazil by the Chinese, clearly shows China’s growing interest on agribusiness products, bringing investments from companies such as COFCO, Tide Group and LongPing High-Tech, ranging from the commercialization and supply of agricultural products to the manufacture of chemical products for the agribusiness. China also increased its presence in this sector indirectly, through the purchase of large multinationals present in Brazil. Dow AgroSciences Seeds and Biotechnology Brazil, for example, sold its corn seed operation to the Chinese group Citic Agri Fund Management and its subsidiary LongPing High-tech Agriculture. LongPing is the seed market leader in China and the world leader in hybrid rice seed production.

There is an enormous difference between Chinese investments in Brazil and Brazilian investments in China. The latter are relatively stationary and not much references and information are available. The China-Brazil Business Council (2012) reports that total Brazilian investments in China reached 27 sectors and 57 Brazilian companies were identified with presence in the Chinese market. Among them there are service providers (50.9%); manufacturers (28.1%), like EMBRACO, Embraer, and WEG; and processors of natural resources (21%), like BRF – Brasil Foods, Marfrig, Petrobras, and VALE, among others. According to CBBC, investments are diversified but none of them represent Brazilian big companies involved in sectors considered to be strategic by the Chinese government such as: new energy, renewable energy, advanced machinery, new generation information technologies, and communications.5

Apparently, it is China that determines the nature and pace of its relation with Brazil defined in its Five-Year Strategic Plans, the last one, the fourteenth, released with ‘pomp and circumstance’ in March, for the period 2021-25. Nesse novo Plano fica mais evidente o objetivo estratégico de expansão dos investimentos “indo para fora” dos capitais chineses, incluindo a prioridade do Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) que envolve 126 países, situando relativamente a posição do Brasil, diferente do período anterior em que a China era predominantemente exportadora de manufaturas e importadora de energia, alimentos e produtos primários. Brazil “without plans” seems to have a passive role, lacking a strategic agenda in relation to China, in addition to signing letters of intent, in the form of strategic partnerships, that come out of the paper only under the control and rhythm of the Chinese partner.

In the case of Brazil, where a dependent rentier capitalism, associated with the great international financial capital and submissive to the US since World War II, prevails, what to expect?

Under the hegemony of financial capital, natural resource-intensive sectors and the agribusiness sector, Brazil, in the first three decades of the 21st century, is consolidating itself as a primary-exporting economy, importing industrialized goods and technologies, and attracting foreign capital in the form of acquisitions and mergers led by multinational companies, in the case of China by state giants, which inexorably deepen our dependence. The national industry has been dwindling, without industrial policy and alienating its main public assets, with especial emphasis on Petrobras.

In China it can be observed the development of state-owned big companies that are supported and financed by state-capitalist capital markets. Chinese capital markets are intricately linked with state institutions and play an active role in financing the big enterprises, in accordance with national development goals, expressed in the various quinquennial plans. In our point of view, the Chinese model, even with the opening of the capital market in the last two decades, given the strong presence of the State in all senses, cannot be compared with liberal or neoliberal models. Control ultimately belongs to the Chinese Communist Party that regulates and interfere in the economic process when things are apparently uncontrolled – current examples are the energy and the Evergrande crises.

Thus, the pattern of the relationship between China and Brazil that can be glimpsed is of the same type as those traditionally central countries of capitalism built with former colonies and late development countries and which, based on the Marxist theoretical framework, are identified as imperialist relations. In the case of Brazil and, apparently, in other Latin American countries, the contemporary relationship with China takes us back to the all-too-familiar dependency theory adapted to the 21st century.6 However, the difference is that the power relations are between a state’ Chinese-style socialist’ with a dependent country, which is increasingly becoming a primary exporter and complementary to the interests of the great Asian state.

Notes:

(2) https://www.cebc.org.br/investimentos-chineses-no-brasil/

(3) Operation “Lava Jato” was a set of investigations, some controversial, carried out by the Federal Police of Brazil, which served over a thousand search and seizure warrants, arresting businessmen, many from the construction industry, which culminated in the arrest of the former president Lula in 2018 so that he could not participate in the presidential election.

(4) When one talks about the “Faria Lima” group – the name of an avenue in the heart of the city of São Paulo, where the headquarters of a group of large companies are located, especially those in the financial market – it is a reference to the elite of the Brazilian economic and financial power.

(5) China-Brazil Business Council Brazilian Companies in China: Presence and Experience, June 2012

https://www.cebc.org.br/2018/07/12/empresas-brasileiras-na-china-presenca-e-experiencia/

(6) Prebisch, R. (1950), The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems (New York: United Nations) | Amin S. (1976), Unequal Development: An Essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism New York: Monthly Review Press | Cardoso, F.H. and Faletto. E. (1979), Dependency and development in Latin América. University of California Press.